No products in the cart.

Marketing Is Still an Art (and a Science)

6 min read

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Data-driven decision making has been the mantra of most good CEOs and CMOs over the better part of the last decade. They want all marketing decisions to be based on solid data that had previously not been available but is today in high amounts. But, data can be deceiving. It may lead you in one direction, when in fact the right answer may be completely in the opposite direction. Allow me to explain with this marketing case study from my Restaurant Furniture Plus business.

The marketing strategy when we acquired the company

We acquired Restaurant Furniture Plus in 2018. Up until that point, the founder was largely dependent on advertising in the Google Shopping section, with product listings of all their SKUs. I was curious why they were not advertising in the Google Search section with keywords, and her response was, “We tried for a few months, but the data could not prove it was actually working, so we pulled the plug.” I was hopeful that was an upside opportunity for us…if we could figure it out.

Our marketing strategy soon after we acquired the company

One of the first things we did when we started our own marketing efforts was to build out our list of keywords and begin advertising in the Google Search section (while keeping our Google Shopping campaign live). We thought of all the possible keywords around our products, including chairs, tables, stools, etc., and all variations of those words, including extensions for restaurant, hospitality, wholesale, commercial, food service, etc.

Our initial results were not great

We were perplexed. Our initial results were exactly the same as the founders’ results when she had tested Google Search. The conversion data in Google was telling us it wasn’t working and our agency recommended we shut it off. But, that made no sense to me. I know we had tripled our marketing spend overall, and I could see our revenues rapidly growing with that spend. So, I decided to dig a little deeper into the data.

What we learned from the original data

When I started to “peel back the layers of the onion”, interesting insights were identified. First of all, the overall campaign was not working, but there were pieces that were. For example, generic words like “dining chairs” were not working, because it was largely consumers looking for furniture for their homes, and all the competitive bidders for that space, like Wayfair and Pottery Barn, were talking the advertising costs up to unprofitable levels. But, specific words like “restaurant booths” were doing much better in helping us get to our desired restaurant targets. So, we decided to put all our efforts on those more directly targeted words, and shut off everything else.

Secondly, we uncovered a major attribution problem. Our customers were using multiple devices, starting from a Google search with their mobile phones, but buying from us from their work computers when they got back to the office, where we losing the tracking of where the lead really originated from. So, we immediately turned on Google attribution modeling tools for them to help us learn that our return on ad spend (ROAS) was closer to a profitable 6x, than the unprofitable 2x the original reports were showing, with the proper marketing attribution tracking in place.

And lastly, we were managing our agency to optimize the wrong data metric. We were pushing them to drive an immediate ROAS. The problem with that was the only transactions that happened immediately, were the small ticket online ecommerce orders worth $500 each. Not the big $5,000 offline orders we wanted to be closing, which had a longer 2-3 month sales cycle. We immediately shifted gears and told our agency not to worry about immediate ROAS (we would track that in 3-4 months). Instead, the only data point we care about is driving big-ticket leads into our sales pipeline (that we know won’t close for 2-3 months). In this case, patience for proving ROAS would be a virtue.

What happened after we changed our data focus

Once we uncovered the above learnings and implemented the above changes, amazing things started to happen. Instead of us leaning towards stopping our Google Search marketing efforts based on the initial poor data-driven results, we actually uncovered the true power of the Google Search campaign and started to accelerate our efforts there (completely the opposite of what we would have done based on the preliminary look at the data). And, as a result, our revenues started to accelerate with more big-ticket leads coming into the business. Yes, we had to be patient, waiting for those leads to close over 2-3 months, but our pipeline had never been bigger or healthier, and revenues soon followed.

An interesting twist

With these changes, our desired leads were accelerating so fast, that our sales team asked us to “pull off the gas”, to let them catch up. That allowed us to test something we had never done before in our history: what would happen if we shut off Google Shopping, the main driver of the business to date? I’ll tell you what happened. The business got materially more efficient. Our marketing spend went down, our average order size went up, our quantity of phone calls and orders went down as we lost low-ticket consumers (allowing us to operate with fewer staff members), our ROAS started to grow, and our revenues/profits started to grow with a clearer big-ticket focus. We were doing a lot more, with a lot lower investment. The Google Shopping channel that had been our focus for years, was never turned back on, and we doubled down on Google Search. Completely the opposite from where we were heading, all with a little bit of common sense and a clearer analytical lens.

Concluding thoughts

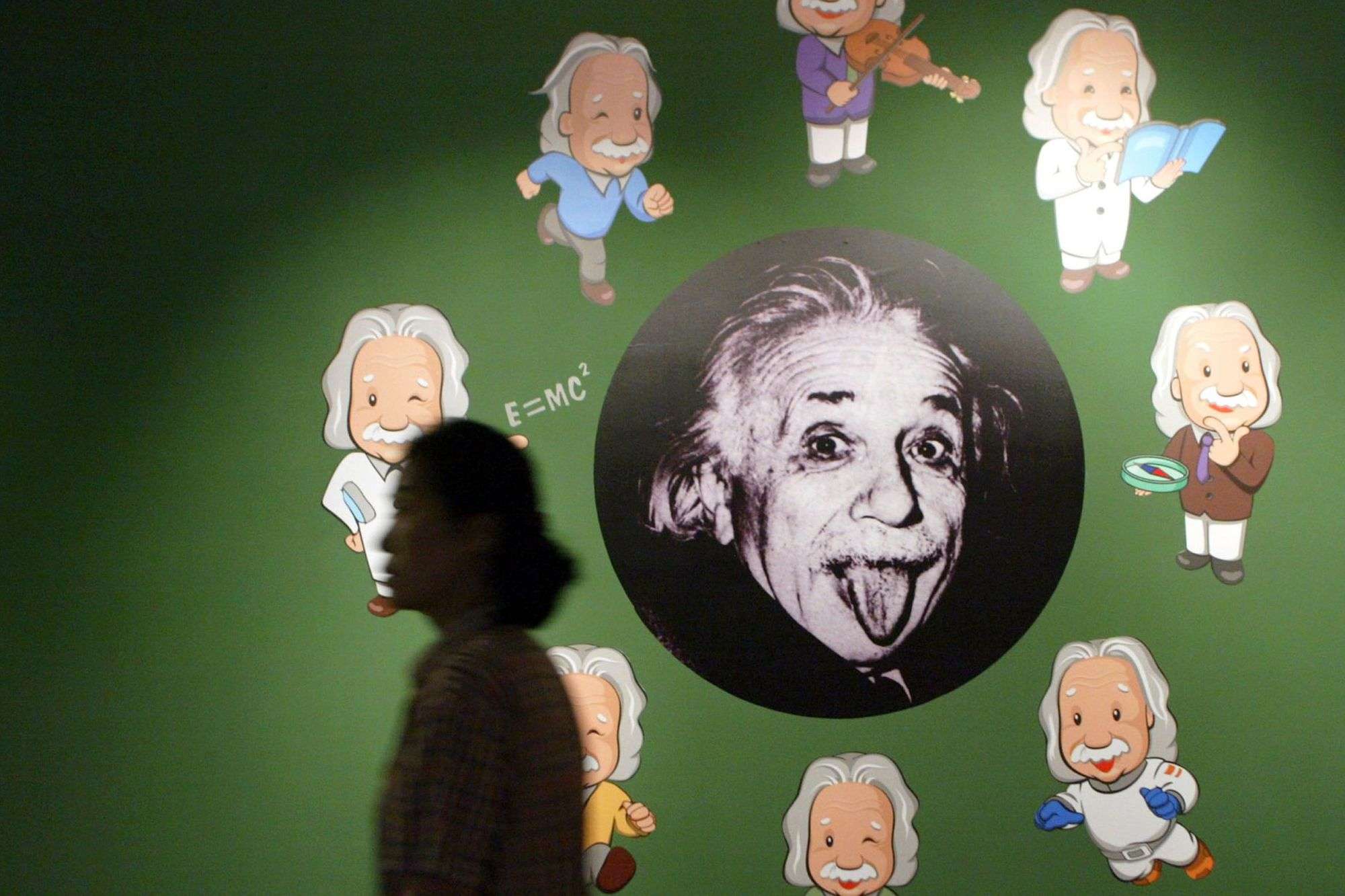

So, yes, data is really important for your business. But, which data points you manage towards, and how you study the data, can make or break your success. For as much as we would like to turn our marketing efforts into a science, it is still very much an art, knowing the right probing questions to ask and still following your internal gut. This case study was an example of Leonardo Da Vinci (art) trumping Albert Einstein (science). Take these learnings into your own business, and make sure you have a good balance of both art and science in your decision making.

This content was originally published here.